December 9th. 2023 Ukrainian shells used today 2496. Russian shells used today 9567… Out of the deluge of information, the numbing vastness of the trivial and the profound, this sobering fact, flickering alone on the screen, got my attention. The Ukrainians are fucked.

The statistic appears in Present Shock 2 (2023) the opening piece in UVA — Synchronicity, a show at 180 Studios by art collective UVA. It’s been 20 years since the group was founded by Matt Clark, Chris Bird and Ash Nehru, and the show is a kind of celebration. Of the three founders, only Clark remains engaged, but the collective approach persists, with the introductory info setting out the groups values: ‘The emphasis on collective labour and shared creative agency, also serves to challenge notions of individual genius or singular authorship, and this impulse is at the heart of why the studio called itself United Visual Artists in the first place.’ I gave them a gold star straight away for that, but what intrigued me more was the £25 entry fee.

The show is billed as UVA’s largest ever exhibition, and the ‘most immersive show in London right now’. It has been commissioned and produced by 180 Studios, and it is interesting to note the commercial basis of the exhibition. We’re all used to paying for immersive experiences; I’ve created a few myself and sold tickets to them. But paying to see art? Despite the proliferation of such projected shows as David Hockney Bigger & Closer, or the many Van Gough immersive experiences, it is still a novelty. Sure, the Tate, The Royal Academy and the rest have put on ticketed blockbuster shows for many years, but these are established art institutions. Art with a capital A, with the exhibitions fitting into a conventional history of the Western canon.

180 Studios are different. Based at 180 The Strand, it’s a media production facility, event space, health club and a few other things. And the show is digital art, a form that still struggles for legitimacy and popularity amongst collectors. So, the venue and show don’t offer the usual Sunday afternoon benediction of Art with a capital A. Instead, the curators have gone for the immersive experience angle, promoting works ‘that challenge our perception of reality.‘ This seems like an interesting development and one that invites a critical response different to conventional approaches that place the work within the artist’s biography, or seeks to explain the work on its own terms. True immersion necessarily entails a consideration of the participants’ experience of the immersion: sensorial, but also emotional and physical. Like a game, artworks that take this form do not exist without the participation of the audience (if they can be called that).

Approached from this perspective the show has limitations. The opening piece Present Shock 2 is probably the most successful of the work shown, but with origins in 2003 (the current piece is a new iteration of an AV piece developed for a Massive Attack tour) it is very much part of a digital art style that was already getting old in 2003. Back then an intimidatingly cool outfit called Onedotzero used to tour programmes of shorts, and publish DVDs. These showcased pop-promos from directors such as Chris Cunningham, and short films like the award winning Who I Am And What I Want by artist David Shrigley. The aesthetic was varied but the work was all very much the product of digital production technologies which were still relatively new. Like Shrigley’s piece, some of the work revelled in an extremely rough aesthetic, pushing back against the hard-edged, hyper real look produced by these new technologies. Much of it, though, traded in technological wonder, the scale and perspectives they enjoyed only possible to produce with machines. Present Shock 2 has the feel of that period, a large LED wall (now that is contemporary) showing vast grids of information scraped from the internet. It is to the piece’s credit that despite the approach now being familiar, it still has an impact, with a contemporary twist of mixing factual items sourced from the internet, with ‘automatically generated news headlines inspired by current news stories.’

To experience the work is to be overwhelmed, to become disorientated without the capacity to deal with the amount of information, and finally numbed to indifference, until that devastating (verified) fact popped up. However, it might be gorgeous and meaningful, but not immersive. At the bottom of a ramp, further down into the bowels of the building, the next piece makes a more convincing claim to immersion. Our Time (2015) consists of three pendulums mounted on a ceiling, each with a cluster of lights on the moving end, set in a line down a narrow space which has a sloping floor. Guessing this was a ramp for an underground car park or loading back. The concrete space is filled with dry ice and visitors can move around below the pendulums. A ponderous soundtrack accompanies the action. The pendulums swing up and down, and across the space, the lights mounted on the end of each varying in direction and effect. It might be a cliche to reference sci-fi in describing digital art, but the pleasing vibe was spaceship launch deck, with the effect slightly diminished by the occasional presence of other visitors. The exhibition notes that the piece ‘makes manifest the relativity of time…’ but I didn’t see, or feel that. The opening chapters of Werner Herzog’s recent memoir does a much better job of meditating on time, and it is curious that the old technology of print is able to do this better than time based media. Speculating wildly here, but I wonder if our perceptions of time are more effectively manipulated through a sequence of words affecting our inner state through the imagination. Alternatively, a sensory deprivation tank might work, but not a light and sound spectacular; our being in the same space produces its own tempo and the piece’s effect merely reinforces this. The act of immersion means the reality is our own, not the work’s. Of course, our perception of reality is manipulated by good immersive work, making us think it is our own. Our Time isn’t able to do that.

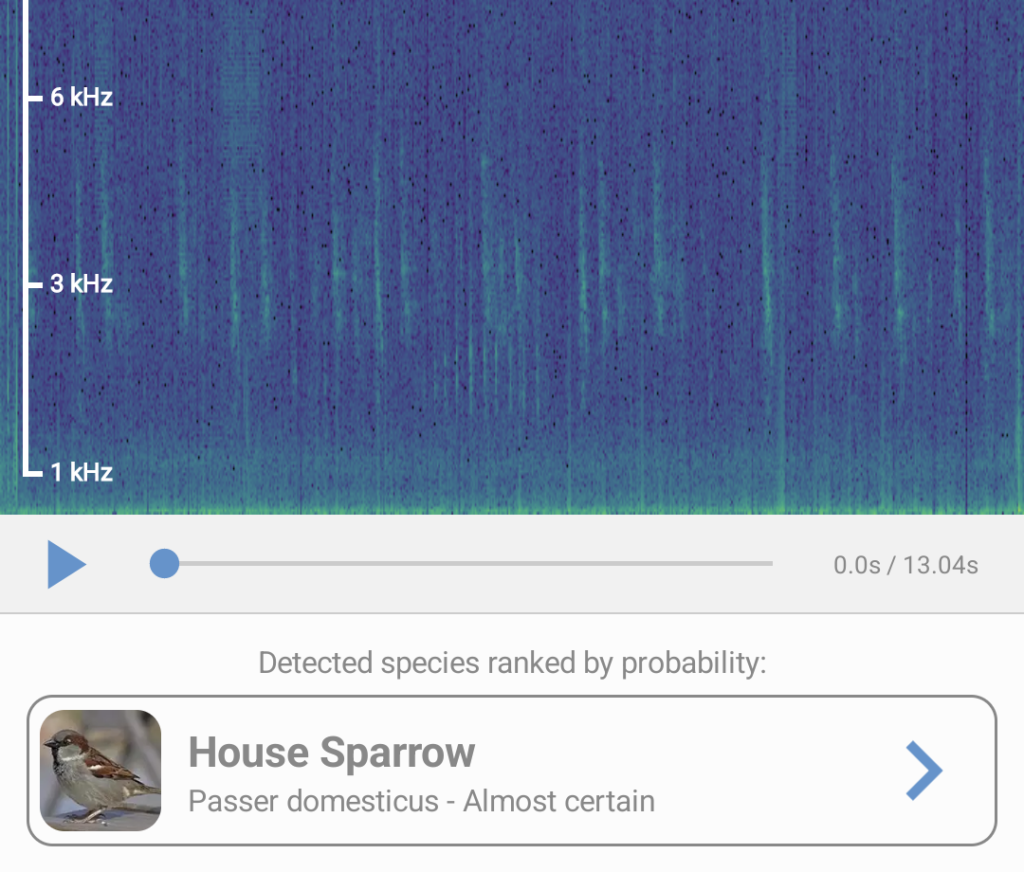

Onwards into the labyrinth. Next up is what Matt Clark has called the centrepiece of the exhibition, Polyphony (2023). This is another remix of an earlier work. I won’t go into the genesis of that work and the subsequent changes, as I want to focus on the physical experience of the piece. I should note, however, that the earlier work had significant input from bio-acoustician Bernie Krause, so there is solid science at play. Polyphony consists of a circle of UVAs signature electronic stele. Connected together, and coordinated, the audio track of the piece is represented by pulses of light streaming up and down from a central point on the stele. This audio, the exhibition notes tell me, has been recorded in the forest of the Central African Republic and features the animals of the forest, along with the calls of the Baku people who call the forest home. It’s undoubtedly pretty and the sound of the forest beguiling, but the visual aspect of the piece is limited. By contrast, I have been enchanted by BirdNet from Cornell University. This birdsong identification app visualises a live audio recording, plotting the sound waves on a graph. Where it recognises the bird, it tags the waveform with the name of the bird. I find the resulting graphic a beautiful representation of the depth and diversity of an aural landscape. A 360 representation of this would be impressive, and the decoding of the audio field incredibly engaging. The climatic effect in Polyphony, the overwhelming of the forest sounds by the roar of modernity, feels simplistic by comparison.

And so to Newtonian physics. Edge of Chaos (2023) and Musica Universalis (2016) are both kinetic pieces, using centrifugal physics to illustrate a number of ideas. Edge of Chaos has a light mounted on the second arm of a double centrifuge; having an offset pivot causes this to rotate at random speeds, as the primary centrifuge speeds up and slows down. The only aspect the creators control is the speed of the primary centrifuge. It is an elegant bit of engineering, a demented anglepoise lamp from Toy Story, as one of my daughter’s friends described it. Musica Universalis is similarly well executed, three globes, each orbited by a moon and a sun, in the form of a lamp. The piece references the ‘music of the spheres’ and the notes claim it ‘physicalises the inherent order of the universe as light and sound’. That may well be, (although ‘inherent order’ is doing a lot of work in that sentence) but as an immersive experience it fails in the same way Our Time fails: the physical fact of sharing the space with the work has an impact, but this has nothing to do with the theme of the piece. Once again, the experience is like being at a music performance: more ponderous sounds, chiaroscuro lighting and dry ice. Some people might like it, some not, but it has as much depth as a mediocre pop record.

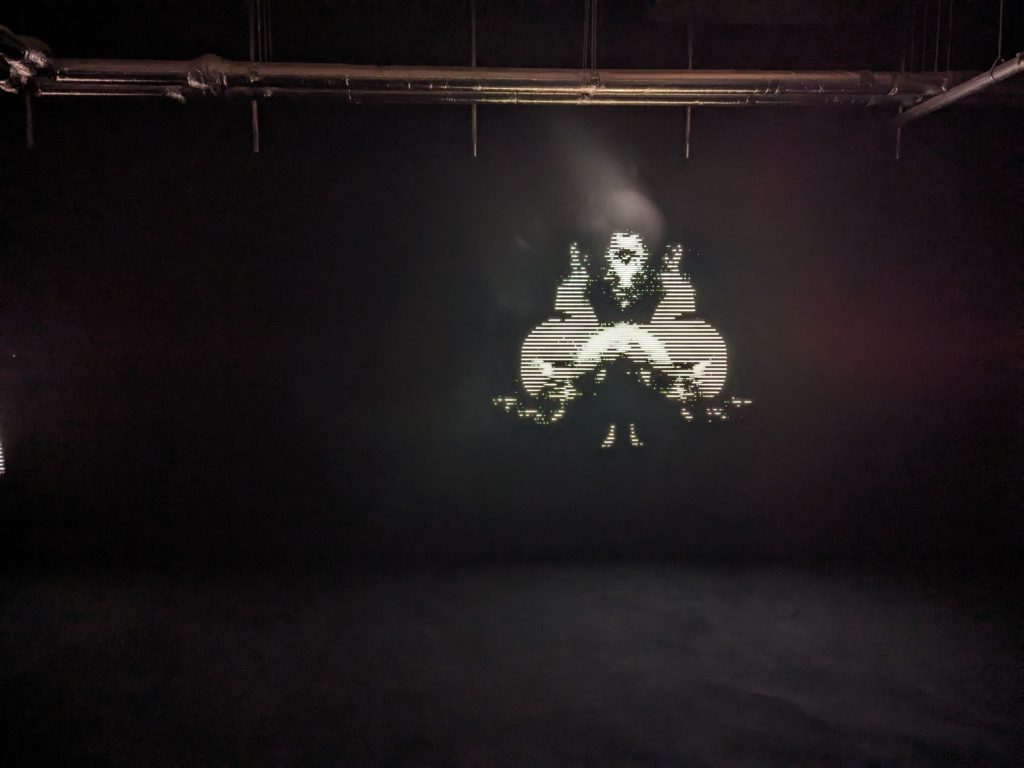

The remaining three works in the show return to the two dimensional plane of Present Shock. LED screens and computer generated content. The early noughties vibes are strong here, pixelated graphics, blocky colour and LED screens masquerading as LCD. Reflecting on them and the work from twenty years ago, the gap between the work and what is claimed for it seems to have become a chasm. On Ensemble: (2023) ‘(it) brings the figure itself into focus in a three part study looking at the evolving relationship between bodily movement and our species’ sense of musicality, inspired by emerging research from the fields of biology, neuroscience, anthropology and musicology.’ It’s pretty hard to see the connection between this and the pixelated video snippets arrayed on the screen. Or, beginning with the work itself, the two adjacent screens showing seemingly random words in Etymologies (2022), the occasion juxtaposition producing unexpected meanings, as is the way with aleatory composition: ‘NEUROSIS’ / ‘FACT IS NOT BEING TO…’ or ‘’NEUROSIS’ / RENEWAL OR BEING…’ (the second screen scrolled and I didn’t take a video). Contrast this with the notes accompanying the work: ‘The deconstructed source material is reduced to lists of interlinked words, creating new associations that reflect on the nature of consciousness, memory, and the process of creation in an automated world’. Hmm.

Possibly the early noughties work had a similar gap between aspiration and achievement, and we just didn’t notice it. Or, maybe the novelty of the technology itself was sufficient; maybe we all thought it contained the potential to carry such hifalutin ideas, it just was a question of time before we finally made the connections. We’re still waiting. Nonetheless, it is encouraging to see new means of funding and exhibiting art work. The format of the immersive experience fits the ephemeral nature of time based work, and it is good to see a new generation of visitors enjoying digital art. Someone should do the same for Anthony McCall, grandaddy of smoke and light.

UVA — Synchronicity runs 12 October 2023 — 15 February 2024

Leave a Reply