It is one of history’s minor points of interest that newly wealthy beneficiaries of industrial innovation assume the imagery, values and lifestyles of the old way of doing things. Think nineteenth century Manchester cotton barons purchasing landed estates and aristocratic titles. In Turin, the wannabe developers of our algorithmically determined future have got themselves an art gallery. A very large, impressive art gallery. The Officine Grandi Riparazioni (OGR) is an innovation hub and tech business accelerator based in what used to be major repair workshops for trains. It’s an ambitious renovation and conversion of old industrial buildings, in a way familiar from many contemporary cities: bare brick walls, sandblasted structural steel, new work and meeting pods in bright colours scattered across the old shop floor.

Around half of the development is given over to multi-use spaces for exhibitions, events and performance. The show Perfect Behaviours (March 29th – June 25th) exhibited in two of these spaces. The exhibition presented work that explored the impact contemporary digital technologies are having on individuals and society, specifically the way machine learning (ML) algorithms moderate information flows, and human behaviour. Clearly, the recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have drawn attention to the potential of these ML technologies, for good or ill, but also occluding the pervasive and malign effect they have already had, with a history closely entwined with the rise of social media networks and ecommerce.

Anxiety about artificial intelligence pervades these perspectives on the impact of technology; what does it do to our sense of being human when we interact with these (semi-)intelligent entities? Rather than machines becoming more human-like, are we becoming more machine-like? It’s a question that has fascinated me for many years; I first tried to answer it in 2002 in my masters dissertation The Mathematics of Desire. So I made the trip to see the show.

The show opens powerfully with Tribes from Universal Everything. An ominous soundtrack accompanies a large projected simulation of the movement of people in crowds. We’ve seen this type of thing often with animated pixel art, but replacing it with figures had an undoubted impact. The problem is the work looks very similar to the paintings of Juan Genovés, a body of work first begun in the late 1940s. I raised this with Universal Everything and their Creative Director Matt Pyke was good enough to reply. He claimed not to be aware of Genovés’ work, and cited this video of crowd simulation software as his inspiration: On checking the dates of Genovés’ work most similar to Tribes, it struck me that given the artist lived to ninety, he could have been influenced by similar crowd simulation software. It would account for the appearance of primary coloured clothing on the figures late in his oeuvre. Matt’s claim in this light seems plausible.

However, regardless of the question of citation it is hard to see what the work adds to that of Genovés, or of Elias Canetti for that matter. This remixing of twentieth century radical art, adding the gloss of projection, and sound and animation, and losing the politics is common. It demonstrates a lack of conceptual and formal ambition. By contrast, the next piece of work in the show, Sociality by Paolo Cirio, reverses this approach. A really important, if dry, piece of online art activism is given a very Twentieth Century treatment with echoes of Hans Haacke’s ‘Shapolsky et aI., Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971’ where the artist documented the slum property holdings of a prominent Guggenheim board member.

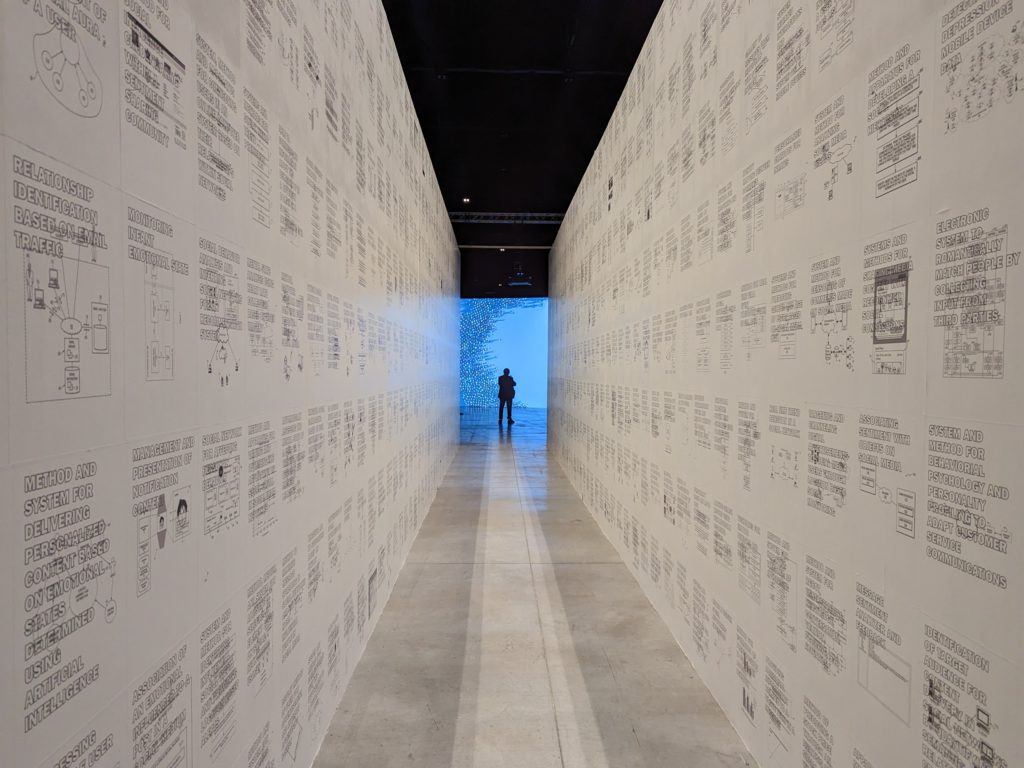

Two walls face each other, in parallel, forming a narrow corridor through which the visitor walks. Each wall is plastered with prints displaying the title of a patent for technology that intentionally aims to analyse, classify, and manipulate people’s behaviour. The patent title is complimented by a diagram of the proposed technology – logical flow diagrams, system topographies, schematics. These illustrations are based on the actual project’s website, where visitors are given the opportunity to vote to ban the technology described. Using patent applications derived from Google Patents, the website is undoubtedly a chilling account of the vast number of ways large corporations have sought to predict and influence human behaviour. It makes a claim for a collective governance system for these technologies, where governments have failed catastrophically to regulate. However, I was at a loss as to why terminals were not available for exhibition visitors to browse the patents and vote on their banning. I took a guilty pleasure in the diagrams (having created many similar ones myself) but the exhibition staging seemed like a lost opportunity.

The next piece, Franco and Eva Mattes’ work The Bots had a similarly powerful premise and form: accounts of the impact of moderating social media on the human agents who provide the labour. Based on interviews by journalist Adrian Chen with staff from a Facebook Berlin office, actors reenacted the transcripts in videos, alternating their accounts with makeup tips. The form is apparently based on strategies used by activists such as Feroza Aziz to evade censorship on TikTok when discussing political issues The contrast between frivolous makeup tips, and accounts of the psychological impact of viewing beheading videos resonated effectively with the idea of human labour attempting to prettify the remorseless stream of algorithmically controlled content. But again I questioned the modality of our engagement with this discourse. The videos were displayed on screens embedded in reconfigured workstations, similar to the ones used at the Facebook office the moderators undertook their work. I couldn’t see how this added to the experience. If they needed to be in a gallery, why not just video monitors mounted in the conventional way, or even projected? This may seem a trivial criticism but it struck me that these works should exist within the channel which informed the aesthetic, such as Facebook, or TikTok. Rather than an audience of the usual gallery visitors, the work could encounter a far broader audience.

The remaining works in the show fitted the gallery format in a more conventional way. Brent Wanatabe’s San Andreas Streaming Deer Cam footage was displayed on four screens. In this already classic work (created in 2015 & 2016) the artist modded Grand Theft Auto to enable a deer avatar to wander autonomously through the game space. Other accounts of the work discuss the way autonomous agents interact within and between themselves without human oversight emphasises our powerlessness, but I dunno. I found myself emotionally invested in the deer, seeing its presence in an urban setting pathetic. There were moments of profound hope as the deer found a patch of open hillside at dawn, as well as horror as it wandered into a sunset gangland shootout. That this story is generated automatically seems less significant.

Like Wantabe’s piece, Toy Prototype from Korean artist Geumhyung Jeong was familiar from last year’s Venice Biennale. This animated assemblage piece consists of a table covered with various electronic components and batteries, so of them configured into animated automata. As with Wantabe’s work, instead of contemplating industrial attempts at humanlike robots, or as the claims of the Biennale literature: ‘Her work occupies an in-between space – a comfort with technology that is uncomfortable, a sensitivity towards objects that is non-consensual, a beautiful and horrifying revelation of techno-social opposition and similitude’, I found myself wondering at the complexity and scale of the human economy and culture that produced such a profusion of stuff. I thought of the factories that manufactured each of the vast number of electrical components present, capacitors, transistors, micro-controllers, and the rest. Why they decided to make that particular item, who performed the labour, what their home was like. The clumsy animations of the dumb automata were unable to answer those questions.

The lack of significant interaction in the exhibition, the absence of something to do, limited the impact of the work significantly, but this shortcoming belied other, more profound issues with the show. Interaction in the 21st Century is no longer simply pressing buttons to navigate a computer interface, but now entirely incorporated into customisation. The interface you see is not the interface I see. Perfect Behaviours understood this, and attempted to portray the aesthetic and understand the ideologies that drive personalisation. The difficulty is how can you report in the third party on an intensely first person experience? In Relational Aesthetics, Nicolas Bourriaud advances a theoretical account of form as it relates to work dealing with human relations and their social context – seemingly a promising toolkit to understand work that deals with behavioural control: ‘Our persuasion, conversely, is that form only assumes its texture (and only acquires a real existence) when it introduces human interactions. The form of an artwork issues from a negotiation with the intelligible, which is bequeathed to us. Through it the artist embarks on a dialogue. The artistic practice thus resides in the invention of relations between consciousness.’ The work in Perfect Behaviours may have met this definition, but at the cost of failing to engage with the nature of experience of algorithmically determined reality. In a world of endless customisation, of individuated experience, a shared work is not possible. This presents profound challenges for artists. It is clear that new forms of art need to be created in order to express the experience of being enmeshed in these systems of control, but also to formulate an aesthetic which arises from these technologies.

James Bridle approached this challenge with their New Aesthetic project, where they noted the emergence of signs and artefacts designed to be exclusively perceived by computer vision. Of course, the endeavour made clear the impossibility of perceiving as another entity, either species or machine, (maybe because of this the project has since broadened to include various idiosyncratic effects of technology), but it was a step in the right direction. So, it was disappointing to come across the final piece in the show, an uncharacteristically banal piece by Bridle: an admittedly striking photograph of a car parked on a pull-in below Mount Olympus in Greece. The programme notes explain that the car is self driving and the road markings that form a circle around it, made of salt, a symbolic material used in magic to contain energy or exclude demons. The intention is to confound the AI that controls the car and imprison it within the circle. This project is featured in the opening to Bridle’s book Ways of Being, and makes (a bit more) sense in the context of the book’s arguments (I’ll be writing more about these in a future post), but as a standalone piece it feels lightweight. This failure neatly confirms my argument: it might represent an occasion for dialogue between the artist and us, but it conveys little significant about autonomous vehicles. A much better piece on this theme I encountered after my return from Turin: How (Not) To Get Hit by a Self-driving Car.

Leave a Reply